|

John Thompson, P.E., is a project manager for Hanson’s aviation market who can be reached at jthompson@hanson-inc.com. |

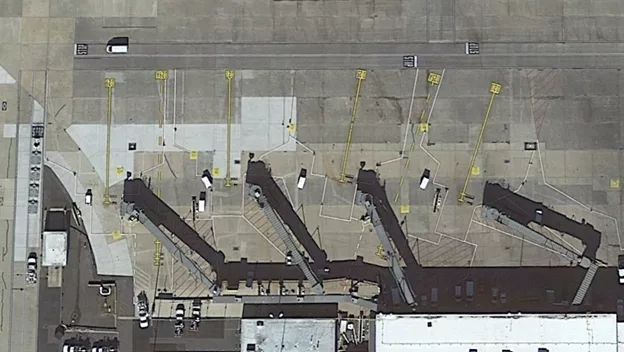

In our December 2022 post, we wrote about passenger boarding bridges (PBBs) and the interface between the terminal and airfield. In this post, we will explore the design considerations for multiple aircraft ramp system (MARS) gates.

The flexibility of two-for-one gates

Commercial aircraft come in all shapes and sizes, from the smallest propeller-powered commuter aircraft to the wide-body aircraft that handle intercontinental routes. Airports are challenged with being flexible to meet the needs of their airline partners while rigidly adhering to the requirements of a broad host of local, state, federal and international requirements.

One of the more recent innovations to meet this challenge is the adoption of MARS gates, which allow the airport and airline the flexibility of using a gate for a variety of aircraft sizes. For example, the airline may have a pair of international flights with larger aircraft that turn (arrive and depart) during morning and evening peak times, along with several domestic flights with smaller aircraft that turn in the nonpeak times and remain overnight. This two-for-one gate scheme allows airlines and airport operators a better return on their investment in PBB and ground services equipment.

MARS gates are arranged in two common configurations:

- two PBBs separated along the concourse, such that only the L1 or L2 (first or second door on the port side of the aircraft) is serviceable on the wide-body aircraft

- two PBBs on a pier along the concourse, such that both the L1 and L2 are serviceable

Both configurations have benefits and drawbacks, with the first type usually more conducive to narrow-body operations and the second type more conducive to wide-body operations. In the first type, the operation of the narrow-body gates is more independent. In the second, the operation of the wide-body aircraft is improved, because two PBBs allow for more efficient enplaning and deplaning.

Realigned for increased success

On a MARS gate where the L1 and L2 doors are docked on a wide-body aircraft, the L1 bridge will extend to a second lead-in line to the right of the primary lead-in line to meet a narrow-body L1 door at a lower elevation. If the ramp depth or width are at a premium, there may also be a third lead-in line to the left of the primary lead-in line for the narrow-body aircraft docking with the L2 bridge.

When planning a MARS gate, the vertical challenge still exists and will have a significant impact on the overall configuration of the terminal and concourse. Selecting the appropriate passenger floor elevation within the concourse will optimize the available ramp space. To stay within Americans with Disabilities Act criteria, a minimum of 12 feet is needed horizontally for every foot of desired elevation change. The greater the difference between your aircraft doors, the more space will be dedicated to passenger elevation transitions.

Thoughtful planning and engineering are critical when designing passenger interfaces at airport terminals. Besides the heavy regulatory environment under which airlines and airports operate to promote safety, there are many considerations for passenger movements, airline operator efficiency and airport management needs. Combining these considerations into a well-thought-out design could save the airport and airlines many headaches and encourage travelers’ continued love of flight.